I'm travelling for a couple of weeks (back around March 15). In the meantime, here are a few hidden gems from the archives.

I'm travelling for a couple of weeks (back around March 15). In the meantime, here are a few hidden gems from the archives.

Enjoy.

The Zercher Squat

This is the first in a series of Timeless Exercises; a collaboration with Run to Win's Blaine Moore. The Zercher Squat.

What is the Zercher Squat?

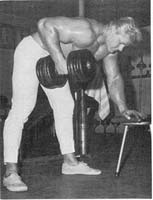

To the uninitiated, the Zercher Squat is a strange beast. Instead of the bar being held across the shoulders (slightly higher or lower for Olympic Weightlifters, Bodybuilders and Powerlifters); it's held in the crook of your arms. The inside of your elbows, if you like.

This is somewhat painful (although you do get used to it a little), however it's an extremely effective exercise. As Louie Simmons notes in Dead Lift Secrets :

It teaches you exactly how to squat. It teaches you to push your knees apart. Push your chest up. Push your buttocks out. The whole nine yards.

Origins

The Zercher Squat was one of the many cruel and unusual exercises created by St Louis strongman Ed Zercher (1902 - 1995). Zercher's own home gym resembled a junkyard more than a basement, and was filled with such toys as anvils, wrecking balls and assorted pieces of machinery. Sounds perfect.

Technique

This is one of the rare exercises where using a thick bar actually makes it more comfortable. A strongman yoke with an adjustable crossbar is great; a thick (2.5" - 3") barbell is also a good choice.

The lift comprises two stages, although it is common to see only the second one being performed in gyms.

The weighted bar begins on the floor, and is deadlifted (using a conventional, or shoulder-width stance) to a point a little above the knee. Aim for the lower quad muscles, rather than your kneecaps.

Slowly squat down; balancing the bar at this point on your lower thighs. Slide your arms under the bar until it reaches your elbows. Now stand up.

Simply reverse the process to complete the exercise. That's one rep.

NB : You may notice that this movement resembles the action of lifting a heavy stone, and it can be a great way to help train for such an event.

How to hold the bar

Regardless of how you hold the bar, there'll be some pain involved. Whilst you can probably ignore it when there's 50kg on the bar, it's a different story when the bar weighs 200kg.

There are three things to consider here. Experiment with them and find the combination that feels right to you. They are :

How your hands are -

- as fists

- clasped together

How your forearms are -

- crossed over

- bringing your hands together

- straight ahead (or at a slight angle)

What the bar is resting against -

- your skin

- a board

- something soft, such as a towel

The videos below show a variety of these combinations.

Videos

The following videos will give you an idea of the various techniques that people are using for this wonderful exercise :

Power Circuit Training

Josh Henkin and Keats Sniderman

(partial Zercher Squat shown)

Zippy Videos

(130kg partial Zercher Squat shown)

Exercises You've Never Tried #18

T-Nation staff

425lb x 2 partial Zercher Squat [streaming, 1.3mb .flv download]

Old training clips compilation from Chub

Other 'Zercher' exercises

There are several other exercises which use the same method of holding the bar. Try a few of these :

- Zercher Lunges

- Zercher Good Mornings

- Zercher Situps

- Zercher Deadlifts (simply start with the loaded bar on the ground, squat down and hook your arms under it, then stand up)

Of course, the original Zercher Squat is still a personal favourite. Definitely a keeper.

Resources

Finnish Power

(thanks Kris)

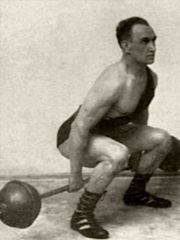

The exercise is usually thought to be named for its creator - or at least the first to openly harness its powers - wrestler George 'The Russian Lion' Hackenschmidt; or 'Hack'. As a wrestler he was seemingly unstoppable; competing in over 3,000 fights from 1889 - 1908 and winning all of them [1]. Yes, he was that good.

The exercise is usually thought to be named for its creator - or at least the first to openly harness its powers - wrestler George 'The Russian Lion' Hackenschmidt; or 'Hack'. As a wrestler he was seemingly unstoppable; competing in over 3,000 fights from 1889 - 1908 and winning all of them [1]. Yes, he was that good. Although it is seemingly self-evident that the name 'Hack Squat' comes from the short version of his own name, Hackenschmidt claimed in

Although it is seemingly self-evident that the name 'Hack Squat' comes from the short version of his own name, Hackenschmidt claimed in  Load up a bar and place it on the floor. Stand just in front of it, with feet roughly shoulder-width apart, and grasp it with a double overhand grip. Stand up.

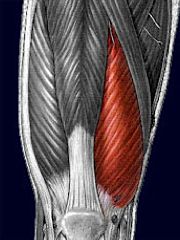

Load up a bar and place it on the floor. Stand just in front of it, with feet roughly shoulder-width apart, and grasp it with a double overhand grip. Stand up. Although this is primarily a quadriceps exercise (especially for the

Although this is primarily a quadriceps exercise (especially for the  As with

As with

Stand with feet wider than shoulder-width (I realise Arnold's using a narrow stance here), with the loaded bar on the ground in front of you. Bend at the waist, bend legs slightly, flatten the lower back, grab the bar with a wide overhand grip and pull it to your chest. The plates should be just off the ground at the lowest point, and the bar is pulled to mid pecs.

Stand with feet wider than shoulder-width (I realise Arnold's using a narrow stance here), with the loaded bar on the ground in front of you. Bend at the waist, bend legs slightly, flatten the lower back, grab the bar with a wide overhand grip and pull it to your chest. The plates should be just off the ground at the lowest point, and the bar is pulled to mid pecs. Dorian Yates famously used a modified bent-over row with great success. The differences from the standard variety are: standing more upright (torso at about 70°), use of an underhand grip (so as to allow more bicep involvement) and pulling the bar to the navel.

Dorian Yates famously used a modified bent-over row with great success. The differences from the standard variety are: standing more upright (torso at about 70°), use of an underhand grip (so as to allow more bicep involvement) and pulling the bar to the navel. Rather than placing one knee on the bench, stand behind the bench and only use a hand for support. The front leg should be slightly bent, the other one a little further back (but straight). Lift the dumbell as usual, but add a slight twist at the top to increase the

Rather than placing one knee on the bench, stand behind the bench and only use a hand for support. The front leg should be slightly bent, the other one a little further back (but straight). Lift the dumbell as usual, but add a slight twist at the top to increase the  I first saw Arnold doing this many years ago - a very impressive looking exercise. With the weight on one end of a bar (and something else holding down the other end), straddle the bar, grab it a little below the plates (with both hands) and pull it to your chest. Note - if the other end of the bar isn't weighed down enough, you won't be having kids anytime soon.

I first saw Arnold doing this many years ago - a very impressive looking exercise. With the weight on one end of a bar (and something else holding down the other end), straddle the bar, grab it a little below the plates (with both hands) and pull it to your chest. Note - if the other end of the bar isn't weighed down enough, you won't be having kids anytime soon. Grab the handle, lean back slightly with legs bent and pull handle to waist. Pull shoulders back, push chest forward and straighten back during contraction. Return until arms are extended, shoulders pulled forward, and back flexed.

Grab the handle, lean back slightly with legs bent and pull handle to waist. Pull shoulders back, push chest forward and straighten back during contraction. Return until arms are extended, shoulders pulled forward, and back flexed.

If you're looking for a little more of a grip challenge than an Olympic bar affords, consider either making or purchasing a fat bar. A typical diameter of a fat bar is 2.5' - 3'.

If you're looking for a little more of a grip challenge than an Olympic bar affords, consider either making or purchasing a fat bar. A typical diameter of a fat bar is 2.5' - 3'. If you've

If you've  Other hooks sometimes used in conjunction with the bar are those which are connected to wrist straps (the

Other hooks sometimes used in conjunction with the bar are those which are connected to wrist straps (the  For dumbbell pressing exercises when a spotter is not present, Dumbbell Hooks (usually

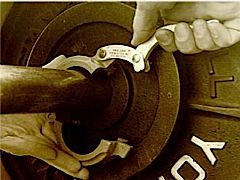

For dumbbell pressing exercises when a spotter is not present, Dumbbell Hooks (usually  Spring collars : I use these for light weights only. They're quick to affix/release, but they tend to move a little when there are heavier weights involved.

Spring collars : I use these for light weights only. They're quick to affix/release, but they tend to move a little when there are heavier weights involved. Key or pin lock (aka shaft or compression collar) :

Key or pin lock (aka shaft or compression collar) :  Screw thread (such as the Spinlock collar) : designed for the threaded Standard bar, these collars are simply spun into position. Whilst secure enough, their one drawback is the relatively slow changeover speed.

Screw thread (such as the Spinlock collar) : designed for the threaded Standard bar, these collars are simply spun into position. Whilst secure enough, their one drawback is the relatively slow changeover speed. Lever locking (such as the

Lever locking (such as the

This is a guest post by powerlifter

This is a guest post by powerlifter